Five thousand six-year terms of Mexican art

(Cinco mil sexenios de arte mexicano).

Javier Fresneda

—Those from Pedrones —they say in Cuévano—

they confuse the grandiose with the big.

—Jorge Ibargüengoitia, These Ruins That You See (1975: 9).

—Does the Pope shit in the woods?

—Dan Houser, Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas (2004).

On October 16th, 2021, the 24-hour deadline to leave the city of Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico granted to the Spanish artist Javier Fresneda Casado, PhD (Segovia, Spain, 1983) will be effective after opening their solo show “Five thousand six-year Mexican art” in the exhibition space “LUIS Galería”, located at Homero 157, Colonia Vallarta San Jorge, in the Minerva district of Guadalajara, Jalisco. So the promptness that I will give to this text will be the utmost.

As an extension of the body of work presented in the show, I was commissioned to write a text complementing the set of controlled inconsistencies [1] representing some of the pieces in this exhibition, being myself, a student with 3 incomplete degrees, who does the “Virgil” role in a journey of “thirty thousand years” throughout the doctoral-level, technical work carried out in a workshop with woods, solvents and enamels in the neighborhood of Santa Teresita, complemented by an extensive academic work developed in multiple collections and libraries in Southern California.

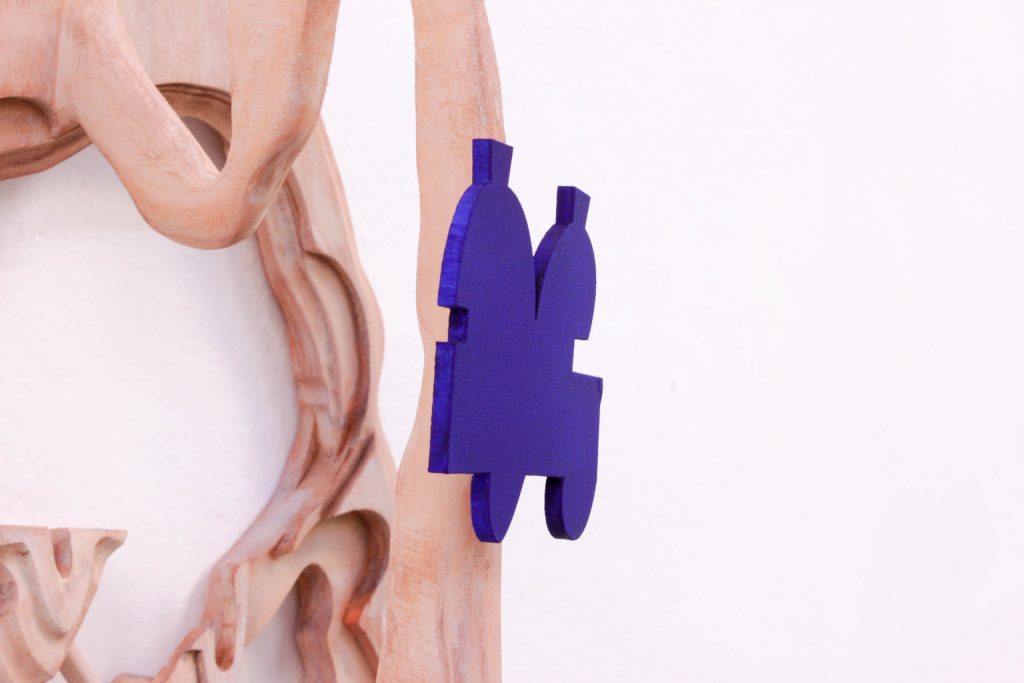

Since the beginning of his professional career, Javier Fresneda has been interested in replicating digital processes within analog environments for the generation of images, which result in two-dimensional and three-dimensional objects that are presented as a kind of physical souvenirs of the Matrix whose “3D printing” it is still made by a hand of flesh and blood. Fresneda’s work represents a bridge between the adult languages of post-internet art from the past decade and the recent babble of stoned formalism [2] that today’s many artists have been drawn on. The ironic bombast of the show’s title contrasts with the small size of the pieces and the exhibition space, as an ironic analogy of many of the silly exhibitions that are presented in Mexican public institutions.

This show receives its visitors with the ass, in the artist’s words, of four horses taken from the Mexican historical narrative: the mounts of Nicolás Bravo (c. 1847), Maximilian of Habsburg’s Orispelo (c.1864), an unnamed horse owned by Álvaro Obregón (c. 1914), and Emiliano Zapata’s Ace of Coins (c. 1919).

Alongside these four horse rearguards, there is a figure that suggests a fifth horse; a concrete fragment taken from the Hollyhock House, a reference to “neo-Mayan” architecture proposed by the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. This piece of stone was stolen during a visit made by the artist to the aforementioned house, and taken to the Yucatan Peninsula to be injected with a mixture of Sikadur®-32 Hi-Mod and ashes extracted from a ceiba tree located in the municipality of Poc Boc, in the state of Campeche, which was used as a scaffold to hang Mayan individuals during the 1843 revolt at Blanca Flor hacienda, which historically is part of the historic process known as the Caste War (1847 -).

As a transition between the exhibition space’s exterior showcase and the privacy of the interior room, J. Fresneda proposes the museographic resource of two canteen doors, reminiscent of the “Chorizo Western” films made by Joaquín Romero Marchent, which function as a transition element between the two exhibition spaces while reducing the solemnity that could imply the treatment of the artist’s subject matter.

In the second room we can find the dismembered body of a contemporary Macario, baptized as “Placario” by its author, which exists as a subaltern representation from the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, and reappears here as a sum of remains made adornment. A hybrid between B. Traven’s Macario; Roberto Gavaldón and Ignacio López Tarso’s Macario and the misbehaved but always curious 1940’s Pinocchio, presented on the big screen by Walt Disney; currently rethought as some young man in flip-flops and a bathing suit who goes on to assault riding an Italika WS 150 in the streets of any Mexican city.

Vigilant from the corner, hangs a sketch for a failed portrait of Charles V, rendering a greater similarity to the alien from “Alf” 1980’s television series than to the Habsburg. This crossed-reference proposes a quasi-accidental analogy between a head of Spanish imperialism and the alien, “cat-vore” conqueror, now domesticated, adopted by an American family on the verge of the Cold War’s end.

In the guise of “eyes” in Placario’s mask located at the back of the main room, we see a portal similar to the ones we can see in the cloisters of many 16th-century Franciscan convents that were built in New Spain. This motif reappears in the prop “Gatekeeping I” and in the two large drawings found in the room “Untitled (Goggles I)” and “Untitled (Goggles II)”, which show the Virgin of Guadalupe’s plasma’s outline and the glow produced by of Vegeta IV’s transformation to Super Sayayin, a character from the popular anime series Dragon Ball Z.

These are repeated in the sculptural studies series that configure the altarpiece present in the room, which describes, from an apparent innocence in its scale and composition, a periodization in the background of certain images that the artist considers essential to account for the theological dimension (that is, the reading of signs) in Mexican history; the Quauhtlahuitzquilitl thistle, Tezcatlipoca’s tlachieloni or “seeing instrument”, the glow of Vegeta’s transformation and the Virgin of Guadalupe’s plasma. These images, which in most cases act as background, index precisely that figure-background sleight of hand that occurs in the ‘classical’ historical narrative. Vegeta’s aura iconographically updates these mystagogical figures (the flame ‘that burns without being consumed’, the ‘background’ from which the messiah emerges) increasing in all directions this missing footage of Mexican historiography that in this exhibition is counted in thirty thousand years.

Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico

October 2021

Luis F. Muñoz

[1] I propose this category in a mocking way, referring to the “controlled accident” in painting pointed out by David Alfaro Siqueiros.

[2] Zerga, L. (2021) Notes Toward a Failed Historiography, Ediciones Ahogadas, p. 27.